A perfect set of not-eventually-equal reals

(This post is tagged #lolbvious, because it’s one of those things that’s supposed to be obvious/clear/straightforward/true by the usual argument… etc, but just makes you go lol, yeah right)

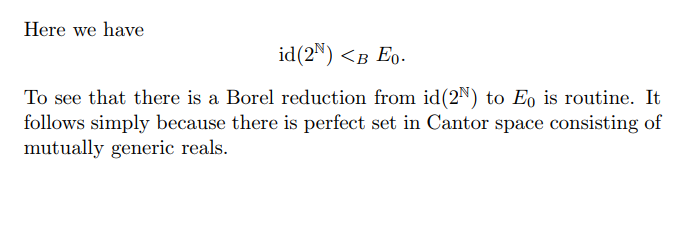

I remember being puzzled by the following passage from the chapter on Borel equivalence relations (by Greg Hjorth) in the Handbook of Set Theory.

The claim is that there is a Borel map $f:2^\omega\to 2^\omega$ that reduces identity to eventual equality. In other words, $f$ is such that

\[x=y\Leftrightarrow (f(x)(n)=f(y)(n) \text{ for all but finitely many } n)\]It is well-known (or maybe I should say well-documented?1) that the existence of such a map is equivalent to saying that there is a perfect set of inequivalent elements for the following equivalence relation denoted $E_0$:

\[xE_0 y \Leftrightarrow x(n)=y(n) \text{ for all but finitely many } n\]which is to say that $x$ and $y$ are eventually equal.

Hjorth says it’s routine to prove the existence of a perfect set of mutually generic reals in the Cantor space. This is puzzling at first glance: mutual genericity is a notion in forcing, which is typically used for proving consistency results, instead of existence.

It turns out that this is one of those cases where one can prove an existence claim using forcing. The trick, of course, is to appeal to Shoenfield absoluteness.

To see this, consider the statement: there is a perfect set such that any two elements are not eventually equal. Now perfect sets are coded by perfect trees, which can in turn be coded by a single real. So this sentence is really saying that there is a real coding a perfect tree, such that any two branches (i.e., real numbers tracing these branches) are not eventually equal.

Since it is arithmetic to say two reals are not eventually equal, this makes the statement $\Sigma^1_2$. So if we can force this, this already holds true in the ground model by Shoenfield absoluteness.

But then this is easy to prove: the forcing to add a perfect set of Cohen reals2 will make this true. This is because the perfect set of Cohen reals will all fail to be eventually equal with one another: if some $c_1,c_2$ are eventually equal, then from $c_1$ we can define $c_2$ by only chaning $c_1$ on some finite initial segment. That will contradict the fact that $c_1$ and $c_2$ are mutually generic.

So I think this is what Hjorth means to say with mutual genericity.

Of course, since Cohen forcing is essentially a Baire-category method, I’ve committed theft over honest toil by sweeping under the Cohen rug any mention of “dense, meager, comeager”, etc. The interested reader can find an argument using Baire category notions in Su Gao’s Invariant Descriptive Set Theory, Theorem 5.3.1, a stronger theorem which is attributed to Mycielski.

-

See, for example, Proposition 5.1.12 in Su Gao’s Invariant Descriptive Set Theory. ↩

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: