Why is the Kleene-Brouwer order also called the Luzin-Sierpinski order?

The Kleene-Brouwer ordering refers to the ordering on $\omega^{<\omega}$ (or finite sequences of any linearly ordered set, really) which is like the lexicographic ordering except that end-extensions are placed below their initial segments. In other words, for $t,s\in\omega^{<\omega}$, $t<_{KB}s$ iff either

- $t$ properly end-extends $s$, or

- there is some $n$ such that $t\upharpoonright n = s\upharpoonright n$ but $t(n)<s(n)$ (Assuming both are defined. This is like the lexicographic ordering)

One can visually think of this as shearing the picture of the whole tree $\omega^{<\omega}$ in the $x$-axis so extremely that it becomes a single line. This is indeed the common application of the KB ordering, turning partial orders into linear orders.

Almost everywhere you look, sources will parenthetically divulge that this is a.k.a the Luzin-Sierpinski order. I’ve long wondered how that is. Turns out this ordering appeared in Luzin-Sierpinski’s 1923 Sur un ensemble non measurable B, yet another classic in the early days of DST.

Luzin-Sierpinski’s 1923 is concerned with defining an :analytic set and proving that it’s not Borel. In modern jargon (assuming the rationals are enumerated as $(q_n)_{n\in\omega}$), the set in question is

\[A:= \{f\in\omega^\omega \mid \exists n_0<n_1<n_2<... \forall i (q_{f(n_{i+1})} < q_{f(n_i)})\}\](It may be instructive to compare this with Luzin’s later simpler example of an analytic non-Borel set.)

In other words, we view a function $f:\omega\to\omega$ as an enumeration of the rationals. The set $A$ is the set of those functions that end up enumerating an infinite edescending chain of rationals (in its usual ordering).

Obviously this set is analytic (I’ve written the $\Sigma^1_1$ definition above). Now this POV wasn’t available to Luzin-Sierpinski, who gave a slightly different definition of analytic set in their 1923 paper, showed that the set $A$ does fit the definition, and then proved the equivalence between their definition and Suslin’s (in terms of the :Suslin operation $\mathcal{A}$).

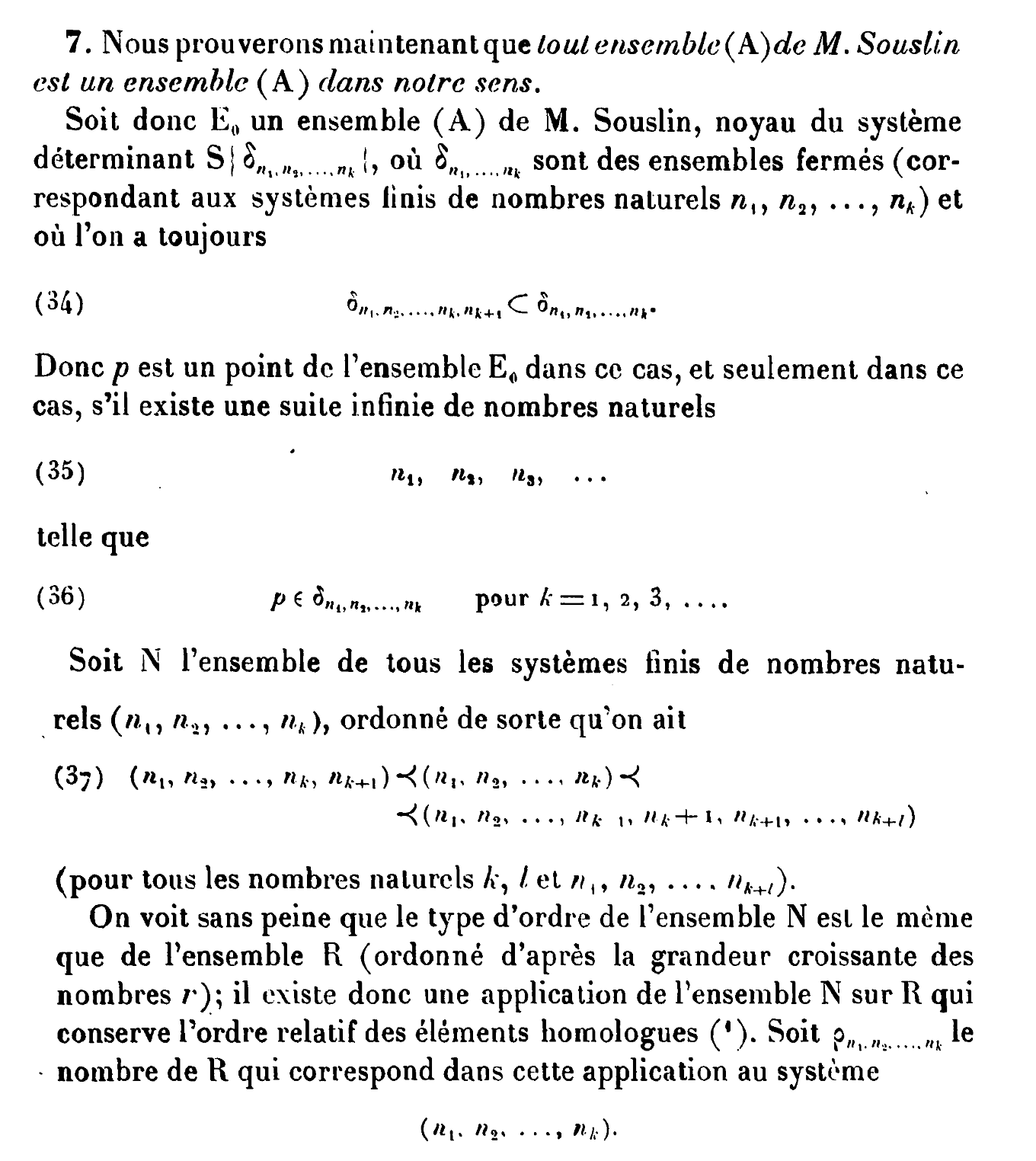

The Luzin-Sierpinski order appears in section 7, when they proceed to prove the equivalence of the two definitions of analytic sets. See display (37) in the screenshot below.

The point is that the definition in this paper used systems of closed sets indexed by rationals, whereas Suslin’s definition used systems of closed sets indexed by finite sequences of naturals. The crux of the proof is to devise a way to order the finite sequences of naturals in the ordertype of the rationals. This is where the Luzin-Sierpinski order comes in:

Fact. $(\omega^{<\omega}, <_{KB})\cong (\mathbb{Q}, <)$

(This is not exactly right, since we need to remove the empty sequence. But you get the idea.) The proof is not hard and apparently ChatGPT can get it right, so I won’t bother writing it down.

For my own taste though, and much thanks to our modern view point, the Luzin-Sierpinski order falls out of a natural attempt to prove that the set $A$ is not Borel.

The key point is that the set of ill-founded trees can be continuously reduced to $A$. This is a common approach of proving an analytic set is not Borel. To find such reduction, we need to construct a continuous function that transforms a tree into a function $f:\omega\to\omega$, such that the tree has an infinite branch iff $f\in A$.

So what suffices to get this function, if you think about it, is to have a map from finite sequences of the naturals (i.e., nodes of a tree) to the rationals, that is order-preserving in the following sense: every infinite end-extension chain in the former is mapped to an infinite descending chain in the latter, and vice versa. The Luzin-Sierpinski order gives us exactly this: any isomorphism witnessing the fact above will do the trick.